Labels Flatten Reality and That Should Terrify You

Walk into a museum or art gallery and something subtle happens. Your voice drops. Your pace slows. Your attention sharpens. You don’t walk through a gallery the same way you walk through a grocery store. You don’t rush. You don’t skim. You don’t reduce what you’re seeing to function. You linger. You let the space work on you.

Now imagine walking through that same gallery and labeling everything the same way.

Picture.

Painting.

Sculpture.

Landscape.

Portrait.

Technically, none of those labels are wrong. But if that’s all you see, you miss the point entirely.

You don’t feel what Van Gogh was trying to communicate when he painted Starry Night. You don’t sense the violence in a Goya. You don’t notice how Rothko’s colors are meant to press inward, not decorate outward. You don’t experience the texture, the restraint, the defiance, the grief.

You’ve named the thing, and now that it’s named… it is flattened.

Labels become a shortcut away from experience.

Art spaces are designed to pull you out of labels and back into sensation. Color is used to evoke emotion. Its absence forces attention toward texture and contrast. Scale is manipulated to make you feel small, overwhelmed, or intimate. The point isn’t to describe the art… it is to encounter it.

Alright, I feel like I’m channeling a bougee, artsy museum curator taking the plebeian on a tour to see some “paintins”

So… you don’t need to be an art historian to understand this. And you’re not meant to live inside the emotional response forever. But the experience reconnects you to something deeply human: presence without categorization.

A brief escape from words.

A reset away from labels.

And yet, the moment we step back outside, we do the opposite… not with art, but with people.

Why We Label at All

Humans label because we have to. Without labels, the world would be overwhelming. Language allows us to compress complexity so we can move through life efficiently. Tree. Car. Enemy. Friend. Storm. Safety.

This isn’t a flaw, it’s a survival mechanism. Categorization helps us navigate danger, organize knowledge, and share meaning quickly. Early humans didn’t have the luxury of poetic nuance when something in the bushes might kill them. Labels saved time. Time saved lives.

The problem isn’t labeling. The problem is when labeling becomes the end of perception instead of the beginning. When we mistake the label for the thing itself.

Calling a Christmas tree “just a tree” strips away everything that matters: whether it’s a Douglas fir or a spruce, where it was grown, who decorated it, what memories are attached to it, why it exists in that space at all.

That loss of depth seems trivial… until it isn’t. Because the same cognitive shortcut that reduces art to “a picture” reduces people to types. And once a person becomes a type, they stop being fully human in your mind.

When Labels Replace Humanity

History is brutally consistent on this point. Mass violence does not begin with weapons. It begins with language.

In Nazi Germany, Jewish people were labeled “Untermenschen”, which means “subhuman.” They were described as parasites, vermin, bacilli, diseases. Rats. Lice. Infections that needed to be eradicated for the health of the nation.

This wasn’t accidental rhetoric. It was systematic psychological conditioning. If a group is framed as a disease, then violence becomes medicine. If they are vermin, extermination feels logical.

By the time physical violence escalated, the moral work had already been done. Language had trained ordinary people to stop seeing their neighbors as human beings.

The same pattern appeared in Rwanda in 1994. Hutu extremists repeatedly referred to Tutsis as “Inyenzi” — cockroaches. Radio broadcasts didn’t urge people to kill their neighbors. They urged them to “crush the cockroaches.” That distinction matters. Cockroaches are pests. Infestations. Problems to be solved.

Within roughly one hundred days, around 800,000 people were murdered. Often by neighbors, friends, and community members who had lived alongside them for generations. This wasn’t spontaneous madness. It was rehearsed.

The Armenian Genocide. Cambodia under the Khmer Rouge. Bosnia. Different cultures, different eras, same structure.

Before every genocide, there is a linguistic rehearsal.

People are not killed first.

They are renamed.

The Rehearsal Phase

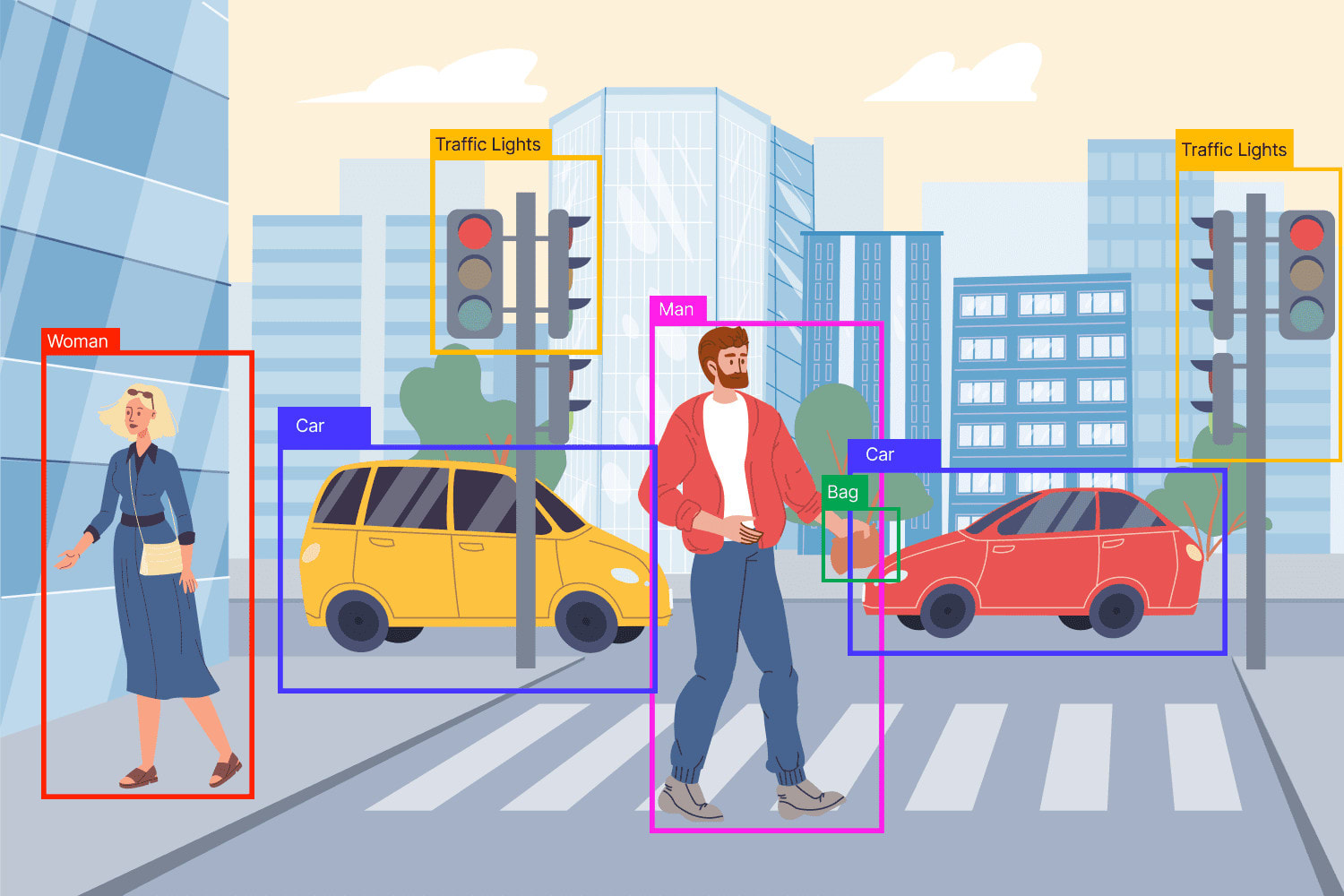

Genocide scholars describe this as a predictable process.

First comes classification — us and them.

↓

Then symbolization — names, stereotypes, shorthand.

↓

Then dehumanization — comparisons to animals, disease, filth.

Only later comes violence. By the time violence begins, it feels justified. Necessary. Inevitable.

As George Orwell warned, political language is often designed “to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.” Words soften the moral edges of action. They create distance between cause and consequence.

This is why euphemisms matter.

Terms like “ethnic cleansing” sound clinical, almost sanitary despite having no legal meaning. They obscure the reality of rape, torture, and mass murder. They dull moral urgency. They make atrocity easier to tolerate from a distance.

Labels don’t just describe events. They prepare people to accept them.

Now Look Around

We like to believe we’re immune to this. But we aren’t. The modern West has been engaged in a quieter version of linguistic sorting for years now.

Liberal.

Conservative.

MAGA.

Woke.

Trans.

White.

Black.

These words aren’t inherently evil. But they increasingly function less as descriptors and more as containers that are preloaded with assumptions about intelligence, morality, intent, and worth.

Once someone is placed inside the container, curiosity stops. You don’t need to ask who they are. You already “know.” And now, another label is floating more freely through the discourse…

Civil war.

Search interest in the term has spiked repeatedly around political flashpoints. Media headlines flirt with it. Social platforms amplify it. Individuals casually invoke it to describe cultural tension or political frustration.

But here’s the inconvenient truth… By every serious academic definition, we are nowhere near a civil war. Civil wars involve organized armed groups, sustained violence, territorial control, and death tolls that far exceed what we see today. Polarization is not the same thing as insurgency. Rhetoric is not the same thing as armed conflict. Some even try to co-opt the meaning to describe a “quiet civil war”. Something happening behind the scenes disguised as periodic mass shootings or meteoric violent politically motivated events that capture the polarization. These aren’t the “New Civil War”. They’re vague attempts to bolster the rhetoric… to capture eyeballs.

Why use the label?

Because labels don’t just describe reality, they shape expectations.

And expectations shape behavior.

When a Label Becomes a Lens

Once “civil war” becomes the lens through which instability is interpreted, every disagreement feels existential. Every election feels apocalyptic. Every opponent feels like a threat to survival.

Fear escalates. Trust collapses. People retreat into tribes. The label creates the emotional conditions it claims to diagnose.

This is how language becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. You don’t need tanks in the streets for society to begin rehearsing conflict. You only need enough people to internalize a narrative that says violence is coming… and that it will be justified.

The Programming Question

This is where you should pause and ask an uncomfortable question:

Who benefits from this labeling?

Conflict narratives are profitable. Outrage keeps people engaged. Fear drives clicks, loyalty, donations, and power. Simplified labels are easy to sell. Nuance is not. When you reduce people to categories, they become predictable. Predictable people are easier to manipulate.

So ask yourself:

Who is encouraging you to see your neighbors as enemies?

Who gains when disagreement becomes dehumanization?

Who profits when complexity is replaced with fear?

This isn’t about conspiracy. It’s about incentives. And the incentive structure of modern media rewards division far more than understanding.

Returning to the Gallery

So let’s go back to the museum.

You wouldn’t walk past Starry Night and say, “Just paint on canvas.” You wouldn’t reduce a sculpture to “rock shaped like a person.” You intuitively understand that something essential is lost when experience is flattened into labels.

People deserve the same respect. The person you label “liberal” is also a parent, a builder, a caretaker, a creator, a contradiction. The person you label “conservative” has fears, hopes, talents, and flaws that don’t fit neatly into a slogan.

When you meet someone, you are not encountering a category. You are encountering a lived human experience, as complex and textured as any piece of art.

Labels can help orient us. But they are not substitutes for seeing.

The Choice in Front of Us

History doesn’t repeat itself because humans are evil. It repeats because humans place emphasis on efficiency… and sometimes efficiency, unchecked by awareness, turns people into abstractions.

The warning isn’t that violence is inevitable. The warning is that labels train us for what comes next. We still have a choice. We can stop renaming people until they no longer feel human. We can refuse to let labels do our thinking for us. We can choose presence over projection.

And maybe… just maybe… if we learn to see people the way we’re willing to see art, we won’t have to learn the rest of history’s lessons the hard way.